A Conversation with Danny O'Keefe (continued)

PM: There's one more thing I would like to touch on with you, and that is: One of the fun conversations I've had just passing through while you're working was that you were telling me recently about roasting your own coffee with a $10 popcorn popper and a voltage regulator.

DO: Yes.

PM: Can we pick that back up for the benefit of the readers?

DO: Oh, that's a good one. It's a good one. What I have done from 1997 until this year, I started a nonprofit, just because I had to start a 501C3 in order to make the project work. It was called the Songbird Foundation. And I think we're going to sunset it this year, because it's largely been successful. You can go into virtually any supermarket, and certainly any coffeehouse, and find organic and shade-grown and Fair Trade Certified coffees. But in 1997, you couldn't.

PM: Ah, so you were at the beginning of that movement.

DO: Yes, with others. And what we had begun to recognize from the work that the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center had done was that populations of birds were declining because their wintering grounds, which are in coffee country from southern Mexico all the way down into Peru, Latin America, that the forests of those countries that were the habitat for the migrating birds and many other species, were being cut to put in essentially crop coffee, produce higher yields, it was a hybrid that did all right in the sun, but it took a lot of fertilizer and a lot of pesticides to make a thrive. It's the basic American farming model, which I'm sorry is as corrupt as anything that exists.

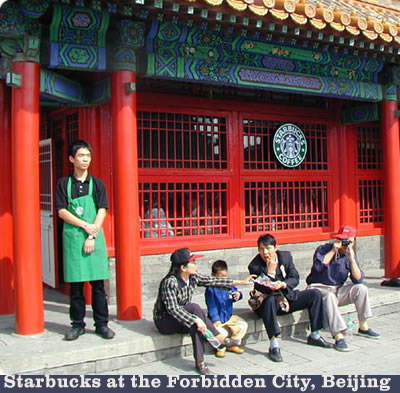

So I knew that if I wanted to work with the coffee people that I better understand coffee at least to some degree. The beautiful thing about the coffee people, particularly the specialty coffee people, like the guys in town here that run Bongo Java, and those kinds of specialty places -- not so much Starbucks, although I have nothing negative to say about Starbucks. I think that they have done a remarkable thing in waking up an awareness and a palate in people for an appreciation of coffee that did not exist before.

PM: That's true. They get pooh-poohed, but they did that.

DO: Yeah, they deserve great credit. And they had listened and they have responded to the environmental and social justice concerns, and I think that they are doing a great deal of good. The people in coffee are very passionate about coffee. Coffee is not like selling chinos or shirts and shoes and stuff. It's a passionate thing -- maybe because it is stimulant in nature, but it is part of our cultural diet, it's a very important part of it, as everyone admits. So it's like with musicians, if you're going to talk to them, you better know something and care something about the music they care about.

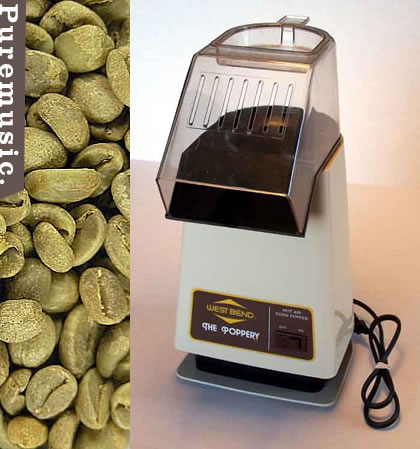

I knew that you could roast coffee -- somebody had told me, and I can't remember who it was, I hadn't seen it done -- but somebody said you can roast it in a hot air popcorn popper. You don't have to have any kind of fancy gear to do it. Westbend used to make these little hot-air popcorn poppers, everybody used to have one. Green coffee beans can be bought online. In those days there was a company called Sweet Maria's that still exists, but there are others now. So I just got some green beans and just started figuring it out. I didn't have the voltage regulator to begin with, and I didn't know anything about it. But there was just something great about roasting coffee.

Coffee is a complex experience, but it's not particularly difficult to roast. It goes through two stages, they're called cracks. And that first crack is kind of like the finger pop sound. And when that's done, there's a little resting period as the heat internally builds up in the bean, and then there's a little rice crispy pop, a little [makes popping noise], and that's about where you shut your machine off and pour your beans into a colander, and stir them to get the heat down, and there you got the freshest coffee in the world. And that's not too dissimilar to how they used to do it in Ethiopia, where they'd just put some beans on a skillet and put it over the fire, and roast them on up, and there's your fresh coffee.

So as I learn more about it, in roasting beans, you learn where they're from, you learn the conditions, the elevation -- all of the things that go into it, the variations of the coffee, whether it's Arabica or bourbon stock, or what's called "tipica," which is slightly different, but they're the older forms, and those were largely shade-grown. They were organic by default, if not certified. And I began to know a lot of the coffee people. And through that it led me to people who were involved in cooperatives and who were the farmers in particularly Costa Rica, but I know people from Mexico as well. So just this great learning experience about a commodity that is one of the biggest commodities that's traded in the world, and one that a great many economies are dependent upon. Costa Rica, I think it's 20 percent of their economy, at least. So it's been a great sort of trajectory of learning.

And the beauty part is that you get as fresh a cup of coffee as you can from some of the finest beans are grown in the world. So I mean, every week I roast up a couple pounds of fresh whatever -- could be a Yirgacheffe from Ethiopia, or it could be one of the nice rich chocolaty coffees from Guatemala. Or we were talking about the Lake Atitlan coffees, which are some of my favorites, Sulawesis -- I mean, there's a world of coffee that is a delight. And when you get really fresh coffee -- and you don't need cream and sugar. It's a lovely drink. Most of what American coffee drinkers drink is stale coffee, unfortunately. And they don't know that.

PM: Right. And over-roasted.

DO: Yes. For all the people who are coffee drinkers out there, if you see oily beans they're already done, they're not really drinkable anymore. So you want a browner bean, rather than the darker oily beans that have no flavor.

PM: Wow. Now what part does the voltage regulator play in the home roasting process?

DO: Popcorn poppers used to be readily available. I think they've been discontinued. But there's still some variation of them around that you can get at yard sales or whatever. But the voltage tends to vary to a degree on them, just because they're made for popcorn and they're cheap. So you can buy a $50 machine, a voltage regulator called a Variac. It's kind of a big weighty thing, but it's a great tool. And it allows you to dial the voltage down so that you can -- it's a way that you can kind of regulate your roast. So if it's starting to go too fast, you just dial it down, and just let the beans take a little bit longer. So you get a longer roast, and it's a more thorough way to roast, and you get more flavor as a result of it. And different beans, depending on the moisture content and some other variables--

PM: So they're all different, every bean wants a little different time to cook before that first crack, for instance?

DO: Yes. And the other thing, too, is that in some coffees you will see careful picking. You won't know it when you see the green beans, but as you roast them, some will remain lighter through the roast. And they were greener picked. You see a lot of it sometimes in the wilder coffees, the Ethiopian coffees, because those will just be -- they're essentially as they were in the beginning, they're sort of wild strains that people go out when it's harvest season and pick everything. I mean, they don't necessarily live out there. And it's time to pick, and then maybe you get another $500 a year if you go out and pick coffee and sell it. So they're trying to educate them a little bit more, but it's still a hard thing if you just don't have that time and you're not getting that kind of profit from it.

PM: Right.

DO: So you'll see those kind of variables. And you can tell the ones that have been more carefully picked, because they'll have a uniformity and more sweetness in the cup. But the wild coffees, the Ethiopian Yirgacheffe, using the Harrars, they have other notes in them, more floral notes and citrus notes that are really unlike any other coffees. I mean, they're my favorites. They're more complex than some people like, but they're great in a blend. They would just bring top notes to a blend that are quite lovely.

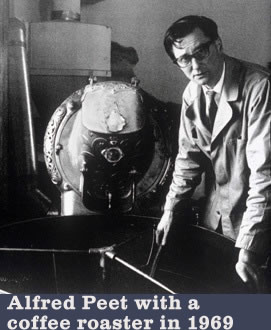

PM: I worked at the original Peet's on Euclid, on the north side of Berkeley.

DO: Oh, with Alfred Peet?

PM: Yeah.

DO: Oh man! There's the guy that started the dark roast.

PM: Truly. And I think I learned as much talking to you about coffee as I did working there, although it was a privilege, it's a wonderful place.

DO: I mean, he's the guy that influenced everybody. There were coffeehouses in New York and whatever, but Alfred Peet really got into it. And roasted dark largely for espresso. You do kind of need a dark roast to cut through milk if you're going to serve cappuccinos and cafe olés and those. And I think he was influenced by the Italians, the Italians tend to roast dark, largely for that reason. He influenced Jerry Baldwin, and some of those people that originally started the very first Starbucks, which was a different company than what this Starbucks that we know. Howard Schultz also -- I may not have this story exactly right [if you're curious, learn more here], but I believe Howard Schultz went to Italy and noticed that people would stop at a little kiosk or little outside coffee bars and just have an espresso and shoot the breeze for a minute and be off on their way, and they would do that several times a day, and thought, there's something here. And I think that those three original guys had tried to leverage their Starbucks, which wasn't an espresso store, they just had the coffees of the world available. And that was an unusual thing at the time to be able to get something other than Yuban or--

PM: Right.

DO: So I think that was what their idea was, though I'm not positive of that, that they were going to take coffee stores around. And I think Howard, what he saw was that there was a coffeehouse concept that hadn't been sort of homogenized for everybody, that here's a place where Grandma and the grandkids can go as well as people who just want to have a nice safe appropriate place to be in. And it was a revolution of a sort.

PM: Absolutely. Well, I was living in Shanghai recently, and there were 60 Starbucks there.

DO: Yeah. And I think Starbucks should be rightfully credited with this: England was a tea drinking country, right, Great Britain?

PM: Right.

DO: United Kingdom. It's now a coffee drinking country.

PM: Is it?

DO: Absolutely.

PM: Oh, I didn't know.

DO: Ireland and England, both, they still have their cup of tea, of course, it's a traditional thing. But there is a great amount of coffee that's being sold and drunk. India, you think of tea. India grows an enormous amount of coffee. And India is quickly moving into a coffee culture -- it's more than a niche. It's becoming a true social beverage, as it is in China. That's a pretty amazing thing. You think of the Chinese as drinking tea. Chinese are drinking coffee cup after cup and think it's a wonderful thing. I'm thrilled for him. He figured something out. Everybody else can carp about him if they want, but that's a pretty amazing thing to figure out how to take a model and globalize it.

print (pdf) listen to clips puremusic home