A Conversation with Danny O'Keefe (continued)

PM: So we ought to talk about Jon Vezner and Mick Conley, who just walked through the studio, and the part they played in your return to recording in the new millennium.

DO: Yeah. I had written some songs with Jon, somebody put us together. But Jon remembers meeting me in Minneapolis when I played a club there. And we went and had some coffee, and he wanted to know about the music business. And he recalls that I was particularly down on it, and just tried to do my best to discourage him from ever getting into it -- which is what I pretty much tell everybody.

PM: [laughs]

DO: "If you want to climb this mountain, you get your own gear and you figure out your own maps, because it will break your heart if you're not careful."

So however we get together, we end up -- the first song that we write -- I have an idea called "Nanna and the Gambler," which is about my grandparents. And I have it fleshed out kind of as a story.

PM: I'm sorry, it's called…?

DO: "Nanna and the Gambler." Yeah, my grandmother, she would not be referred to as "Grandma." If anybody called her "Grandma" they would be likely to get in trouble. "Grandmother" was just a little bit too much, so Nanna. And I never knew my grandfather, but he was one of the last of the independent livestock brokers. He was an interesting man. Had been a cowboy in the late 19th century. He was a man who could put a herd together, so he was a livestock broker. But hardly anybody knows what that is anymore, because you don't see anybody put herds together. But it's an art.

So in that discussion of reading the lyric or whatever, discussing it, there was some line about hard words. And Vezner said, "Hard words are easy to say." Well, there you go. And then we were off. And it's a great song. My hope is that somebody will cut that song and make it their own.

PM: A great idea.

DO: Oh, it's a beautiful song. It's one of those songs that it just has resonance in the audience that everybody knows.

PM: Right. You get it right off.

DO: Everybody's got those pictures on their walls that they still say I love you to those pictures, and they wish to hell they'd sent them to the people that were there when they were alive. We all have that.

PM: So did "Nanna and the Gambler" ever end up getting written, or did it turn into "Hard Words"?

DO: It turned into "Hard Words."

PM: Wow. I love that about songs, it starts here and it goes there.

DO: Yeah. And I think I had the line in it that, "I love you were the hardest words of all," right, which unfortunately, they are. We say it too infrequently.

PM: And when we do say them, it doesn't mean as much as the places where they truly belong and go unspoken. They're said more casually than in the crucial instances they need to be said.

DO: Right. Because in that emotional bridge, that is the place that it's most often difficult to say anything. It's a tacit understanding, if it is understood.

PM: And somehow your co-writes with Jon led to Mick Conley.

DO: Mick Conley was Kathy Mattea's engineer. And Jon is a fan of new technology -- which I'm not. I'm the most primitive person in the world when it comes to technology. And he had had somebody build him a computer, and he had found a company -- I think they were from Minnesota somewhere -- that were making digital recording equipment. I don't even remember what their names were anymore. And we had enormous problems. And Mick had never used a computer in his life, and he learned. And so we were just in Jon Vezner's basement, and I'm not figuring it out, I'm just--

PM: Watching.

DO: I'm just playing.

[laughter]

DO: And I had some demo tracks that were still kind of recoverable, the basic tracks in them were kind of usable. And we cut some new tracks. We went out to Hendersonville -- Mick could tell us the name of the studio...

PM: Oh, Paul Martin's studio.

DO: Paul Martin's studio, yes. So we cut a bunch of stuff there that was really great.

PM: Clubhouse Recording. [cat’s amazing, check it out here]

DO: That was just Paul Martin's basement, but it was just -- the great thing about Nashville players is that, first of all, there is a wealth of them. And for the most part, they come to play. And they have an economy of playing, but they also have a wealth of creativity that often doesn't get used, if they're just being asked to play stock charts. So you add an augmented chord and maybe a couple diminished here and, and more than a minor or two, and all of a sudden they start to blossom. So you can have a lot of fun. I love to make records that way. Instead of walking into everybody's favorite session band that gets the call all the time, let's see what these guys got to bring.

And those sessions were fun. We had trouble with the computer, which was a source of aggravation to all, but in the process we got a good recording out of it, which unfortunately got picked up by a company that went out of business almost as soon as it opened its doors, and then the parent company went bankrupt, I mean, I think as -- well, I can't say that it was theft, but...

PM: But it seemed a little shady.

DO: It seemed wrong, in any case. Right? So that record got buried for five years, which was really unfortunate. I'm hoping that I can find somebody that is interested enough in redistributing it.

PM: And which one was that?

DO: It's called Running From the Devil. And I love the songs on it. It was the first time since 1984 where I'd actually been in the studio with new material -- and that was 1999.

PM: Right, because Redux was just simply that, right.

DO: Yeah, there's nothing new on that, yeah. And in fact, those aren't even remixes, because we had lost the original 32-track tapes from Day To Day.

PM: Ouch.

DO: They had been awarded somebody who was owed money by the people who financed it, and he walked away with them or lost them or something. But even if we had the money he didn't know where they were, and we could never recover them.

PM: Unbelievable.

DO: And unfortunately, it was largely made on a synthesizer package, so the drum machine and the whole thing and all -- I mean, you hear it now -- I love the songs, but I can't stand to hear some of the sounds. You know, the Linndrum sound from--

PM: Yeah, the early digital days were pretty painful.

DO: Yeah. So I'm actually going to retire that record, I think, and hopefully re-record some of the songs.

PM: But it led to more better computers and much better experiences with today's technology and recording with Mick Conley, and which brings us here to our studio today.

DO: Yeah. For the people that don't really understand the growth -- I mean, you can see it in your own personal computers, where a megabyte used to be precious, a gigabyte was unheard of--

PM: Right.

DO: -- at least in personal computing. And now you go down to the store, and, "I'd like to have a 200 gigabyte hard drive, please."

PM: "And I want it cheap, too." [laughs]

DO: Yeah. So the system that we're working with here, the Nuendo system, and this room, we never had that. And it isn't that it's necessarily faster, but it gives you this incredible ability to enrich the sound. I mean, I think that what we have is a fairly basic recording that sounds really rich.

PM: It's unbelievable. I've been listening to the tracks you've been working on, and it's so lush and so orchestral, and so really complex without sounding complex. And I see now going back through your work that that aspect of your work was there from the very beginning, even though there was a kind of rootsy, rock 'n' roll, folky guy at the beginning, that compositional complexity was there right from the top, because as you say, the jazz influences, for instance, were always a part of where you were coming from.

DO: Yeah. That's still what I listen to. I mean, for the most part, I don't listen to peers -- I mean, I'm happy for them, but I'm not interested in being influenced by them.

PM: Right. When we first saw each other, and before I turned the machine on today, you were telling me that Marty Stuart came over last night for a session.

DO: Yeah, how great.

PM: How did that go?

DO: Oh, it was wonderful.

PM: How did that come to be?

DO: Again, Mick Conley. It's all this close circle of friends. Mick Conley does sound for Marty, and has recorded some stuff with him. We heard a track last night that Marty had recorded with Mavis Staples that Mick had engineered, and it sounded great. And I think that Mick had mentioned to Marty that we were doing some stuff together, and maybe played him a taste or two or rough mixes, and Marty, just out of his generosity said, "Well, if I can be of help, I'd love to be involved." And Mick said, "Well, in that case, why didn't you come on over and bring your mandolin?" And we just sat down together and played a song last night.

PM: And so what did you play?

DO: A song called "The First Time." It wasn't on the original dozen songs that we had planned to record, but it's a song that whenever I've played it, people have come back afterwards and said, "Where can I get that?" And it's kind of a biography in a song -- not necessarily mine, could be anybody's biography. But it's a biography in however many verses and a chorus and a bridge. And it's a good song. And we just played it very simply.

PM: Did you play it on guitar?

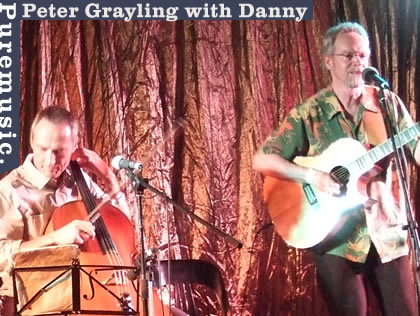

DO: Yeah. He played mandolin, and I just played acoustic guitar. And it's a live recording, in that sense. We sang and played it three times, and the third time was the one we liked the best, but the first one was okay, too. We just decided to go with the third one. And Mick's wife, Terry Wilson, who is a wonderful singer, was the person who is singing all the harmonies on this new record, and she's a great singer.

PM: She's fantastic, love her.

DO: Yeah. She's incredibly inventive. I mean, I didn't tell her anything, I just said, "You just sit, and whatever you come up with will be fine." And so she and Mick just worked at their house on the computer. And every once in a while I'd get something and it was like, "Whoa, that's nice."

It's a luxury to be able to work with people that you have complete trust in the kind of decisions that they'll make, and just let them be musical. Don't have preconceived ideas. And that's largely where you get the nicest tones and hues.

print (pdf) listen to clips puremusic home