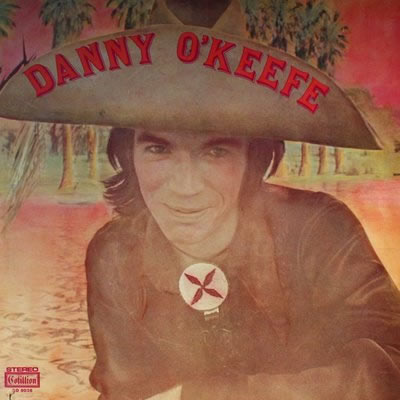

A Conversation with Danny O'Keefe (continued)

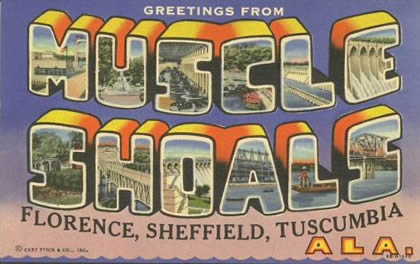

DO: And Atlantic had given them or sold them, or whatever, an eight-track Scully that was used gear for them. So they had an eight-track Scully, and they had players. And Muscle Shoals was funky. I mean, I don't even know anything about Muscle Shoals. I just went to the Holiday Inn and I went to the studio, and that was it. And two days later I was gone.

PM: And who was there when you got there? Who was on the scene?

DO: Well Solomon Burke was just paying his bill.

PM: Damn!

DO: He had just finished cutting his tracks and doing his vocals. And I think he was going to do horns someplace else. But yeah, he was just there, saying his goodbyes to Ahmet. And R.B. Greaves was up before me, and he cut a single called "Take A Letter Maria."

PM: Wow.

DO: And I'm on next. It was like one right after another.

PM: Damn!

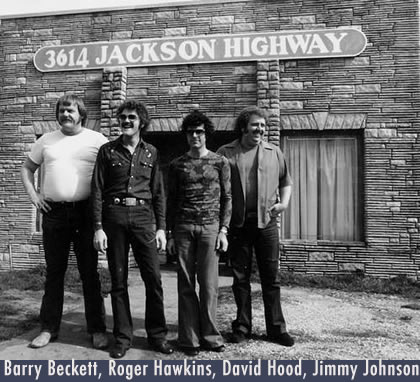

DO: I mean, obviously Barry Beckett was playing piano, and Roger Hawkins and David Hood on percussion, and Eddie Hinton was playing guitar. I mean, I'm just this greenhorn from the northwest that -- I don't know anything. "Here's my song." "Okay."

PM: And you're in there to cut "Charlie" and "Steel Guitar."

DO: Yes. And the thing is that unfortunately that version of "Good Time Charlie" is not the single. When you hear it now, it's--

PM: That's the one with the flute, as it's called?

DO: Yeah, the flute. Where I ever got that idea, I just haven't got a clue -- except I think because we had a flute player in the original idea for that band, and he played along, and there was a conga player... That was kind of the arrangement that I'd had in my head.

PM: It was kind of almost a beatnik-y arrangement with the conga and the flute.

DO: Yeah. And it was a funny scene where Dan Penn and Spooner [Oldham] came in, and Dan Penn said, "You really need to put some vibraphone on that, some marimba on that." "Marimba? I don't think so." But he might have been right. It might have been a great sound on it.

PM: Did Spooner have anything to say?

DO: I just remember Spooner being there, but I don't remember him saying anything much, other than maybe just idle chat. But it was Dan specifically because he knew Ahmet and he had an idea.

PM: Right.

DO: They were just there briefly and they listened to the track, probably because Ahmet wanted--

PM: He said, "Come on down and take a listen to this."

DO: Yeah. He wanted to probably hear what Dan had to say about it. So I mean, the thing is that Ahmet is a force of nature. And I'm sure he would admit, that he probably was not a great record producer, because that's really not where his talent lay, and he just was too busy. To have him in Muscle Shoals was one thing, because it was fairly isolated, and it's many years before the cell phone. There was no way that everybody could get to him. As soon as he was in L.A. -- and we cut half the sessions in L.A. -- then everybody could get to him. So he had phone calls stacked up. And L.A., he's at the Beverly Hills, and everybody in town wants to see him.

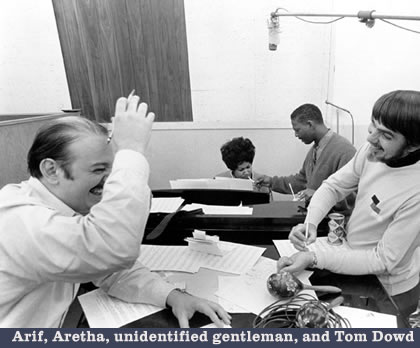

That first record was a really great schooling, a wonderful opportunity that was afforded me. We had a little bit of airplay from a song called "Covered Wagon." That was about it. I didn't know anything about touring. I didn't have a band. We kind of just went to the next record. The great thing in those sessions in New York was that he brought in Arif Mardin to help with some of the mixing, largely because he was too busy, and also because in Muscle Shoals they only had eight tracks. So for instance, on the drum track they put the piano. "Well, I'd like to hear some more piano -- no, not as much drums. Just some more piano." "Oh, thank you."

PM: That's a problem.

[laughter]

DO: So yeah, those kind of problems in those days, it's years from all the virtual tracks that you can bring to bear now. So that's just what we had. So they suggested after that that for the next record that Arif be the producer.

And at that point we really don't know each other. I think we've only just kind of met, right, and that's all. Not even any real conversations or anything. So I just meet him in Memphis, right? And we're going to record in American Studios, which is Chips Moman's old studio.

PM: Right.

DO: And all of those guys, wonderful players, Reggie Young and all those guys.

PM: Right.

DO: Mike Leech and everybody from that era, in that studio. I just fly down there and go directly to the Holiday Inn, and the next morning, whatever, we go to the studio. And it's just ping, ping, ping, back and forth. But again, really creative guys. I mean, I love that kind of thing, you just walk into a studio with guys that can play, and run the song down for them. I don't write music, so it's going to be head arrangements.

PM: Right, just run it down live.

DO: Yeah. And in a real sense, it is the essence of folk music, it's different instrumentation, but this is how we make folk music. We just start to pick, and somebody has an idea, and before we know it somebody says, "Hey, let's cut that." The great thing was that Arif, I think more than anyone else -- Ahmet may have suggested and known it, too, but we all knew that "Good Time Charlie" was a hit.

PM: Everybody knew that.

DO: I think so. We knew it originally, we just didn't have the arrangement.

PM: Right.

DO: So Arif brought to bear not only his arranging skills, but a sense of economy to it. He knew how to get it compact enough that it was right. And I mean, that is the great thing that he did for me -- besides Breezy Stories -- but just making it possible to go on, in a real sense, creating a real fit.

PM: Getting that totally right.

DO: Yeah. And the great thing about it was that it started in country, so it had some country respectability.

PM: Oh, it started as a record in country?

DO: Yeah. It started playing on country stations and got up above the 20s, but I don't know -- I have no remembrance of where. But it might have got to 18 or something, I think, at the most. And then they crossed it over.

PM: And to do that, they what, engaged a whole different team of promotion guys?

DO: This wasn't Atlantic at this point. This is in the era when custom labels...

PM: Right.

DO: And this to my endless chagrin, I had an opportunity to be one of the first artists to sign with David Geffen, and I didn't do it. I just chalk it up to bullheadedness and stupidity. I should have just had a lawyer and worked the contract out.

PM: You just got shown something and didn't like it and moved on, or--

DO: Yeah. I moved downstairs to a label that was run by Artie Mogul and Ron Di Blasio called Signpost. They were fine fellows, but they were not the visionaries that David Geffen was. And David Geffen had learned a great deal from Ahmet and others, right, but he was and remains one of the most astute people in the media arts.

PM: What was he like as a person back then? Was he a very aggressive guy? Very self-assured?

DO: Well, I think he was very self-assured. I think he's always been self-assured. I think that's who he is. I mean, he was an agent at CMA, and he was a great agent. He had Joni Mitchell and Miles Davis. I mean, he worked with the artists that he believed in and wanted to work with -- Laura Nyro -- great artists. But he was plotting and planning. And I think that he and Ahmet had been plotting and planning, and Ahmet knew that he would be a good record man because he understood that generation of artists that was coming up in a way that maybe Ahmet appreciated, and maybe didn't. It's a generation of songwriters, so much different than the generation of rhythm & blues and jazz artists that had been predominant prior to that, that Ahmet and Wexler both really understood well.

Artie Mogul was a good record guy. He understood how to make a record and keep it moving. The problem was that he got in a pissing match with Ahmet, and that was a big mistake on his part, God rest his soul. Ahmet is nobody's fool, and Ahmet owned the company. Right? And Ahmet didn't give a shit if Artie Mogul had been band boy for Tommy Dorsey. It didn't matter. Ahmet was the son of the Turkish Ambassador to the United States.

PM: Was he?

DO: Yes, he was.

PM: Hello.

DO: In World War II. And believe me, that was one of the very important liaison positions.

PM: No doubt.

DO: The Dardanelles were very key.

So essentially, the single did well. I mean, it got into the Top Ten on both Billboard and Cashbox. The album was shelved because Ahmet basically told Arif to walk, and dropped the label -- or let him take the label wherever he was going, which I think was at Universal, where he found a home. But Ahmet wouldn't let him take the record. He said, "Atlantic owns that master. They only licensed it to you." So the record was gone. The album was gone.

PM: Damn.

DO: I mean, after that there was nothing but cutouts. There was no promotion after that. I think they tried to release "The Road" as a single. The thing I would say for David Geffen, that I certainly -- I didn't know well enough for myself -- David would have made that album -- insisted on that album being richer in so that, "Yes, 'Good Time Charlie' is the single, we know that, what's next? Can we be two or three deep?" Maybe not exactly in Top 40 radio, but FM was just beginning to become a strength.

PM: Underground radio, right.

DO: So what have we got that we can create a foundation for a career that radio will appreciate rather than just a one-off single, and goodbye. Right? So I mean, that's very important thing in a company. A lot of companies don't nurture artists anymore--

PM: Absolutely not.

DO: --because they don't have the interest, and it isn't how the system works anymore. You can get one or two CDs, and the group is gone. And if you made money, great, the group remains in debt, but the company made money, and "Bye."

PM: And that's all that counts.

DO: Yeah. So the music business, as you know, is a dangerous place, but it's a fine school.

PM: Right. And if you've got to have it, and if it's in your blood, there really isn't too much choice in the matter. I mean, you got to do what you got to do.

DO: Yeah, if you want to make music.

PM: How many versions of that incredible song ended up getting cut? Do we know?

DO: No, I don't. I mean, I certainly can cite all the ones that I know that are my favorites, from Elvis, to Willie, to Cab Calloway, to Mel Tormé, to Dwight Yoakam. Chet Atkins and Earl Klugh played a nice instrumental version of it.

PM: Together?

DO: Yeah.

PM: Wow. [here]

DO: So I mean, there's probably a lot more than I've ever been aware of.

PM: Right.

DO: I hope they keep cutting it.

PM: Yeah. I hope you get paid for all of them.

DO: Well, I do get paid for "Good Time Charlie." I don't always get paid for the records sold, but I get paid for the publishing, because I have good administrators.

PM: Who is your administrators on that?

DO: Warner Chappell. They've been very good over the years.

PM: That's a good company. I've always heard good things about them. There have been other significant covers, though, of your tunes. I mean, "Souvenirs," right?

DO: Well, I guess it's significant. I wish he'd put it on his own album instead of putting it on the Late Night Cafe of his record label. Jimmy Buffet is who we're talking about. I'm thrilled that he did it. When we let him have it, the implication was that he was going to put it on his own album as well as put it on that sampler.

PM: But that hasn't happened yet.

DO: No. I would have held it back, because I thought that song was a good song, and I thought that song could have been covered by a bunch of different people at the time, and it just... I didn't have much to say about it.

PM: And he did a good version of it.

DO: Yeah, he did, yeah.

PM: So why he wouldn't put it out on his record is a mystery. It was a good version, it's a great song.

DO: Yeah.

PM: Oh, and that was a tune with a guy I like a lot, Vince Melamed.

DO: Oh, yeah. One of my oldest, dearest friends. When "Good Time Charlie" had become a hit, and I needed a band and I needed to go out and tour, Vince and three other guys who have become some of my oldest, dearest friends, and one who I write with a great deal, Bill Braun, were in a band called the Mugwumps -- the other Mugwumps. And somebody said, "Here's a band. Why don't you go over and see if they can play your songs?" And so I went over to some club in Westwood in L.A., and they learned my songs, and off we went.

PM: "Sure enough, they can play my songs."

DO: Yeah. I was just about as green as a person could be.

print (pdf) listen to clips puremusic home