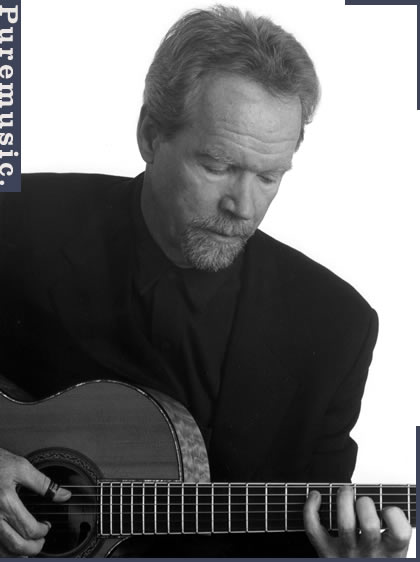

A Conversation with Danny O'Keefe

Puremusic: It's been a real pleasure, though I've not been on the scene, having you at our studio, Danny; it's an amazing happenstance, I think. Whenever I've heard your name over the years there's always been kind of a hushed reverence attached to it in the songwriting or the musical community. On the one hand, you're so highly regarded, on the other hand, it's not that easy to find out about you. There's a rather grand mystique around the man and the artist.

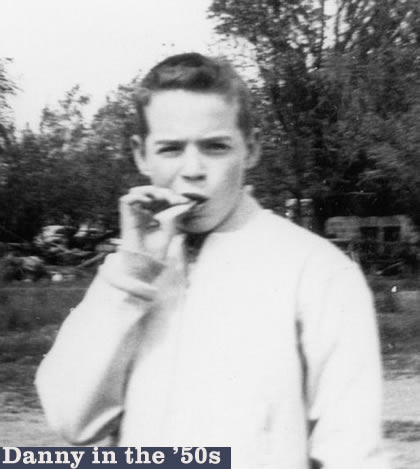

So I started getting acquainted with everything I could that was out there -- in cyber world, anyway -- and was very surprised by some few things that I found. But one thing I couldn't find, for instance, is accounts of early days, what kind of a family and a home you may have grown up in, and what you were like as a young boy, in school and so forth.

Danny O'Keefe: Well, the thumbnail bio is that I was born in Spokane in '43, war years. My father, to his endless sadness and dismay, I think, was 4F. He got through basic training, and then they drummed him out. I think he had lung problems, or had something that was going to be a serious problem, and probably was a contributor to his later poor health. And Spokane really was kind of backwater in those days, but still really beautiful country. We camped -- I didn't hunt that early -- but we fished and all that. In the late '40s we moved to a town on the Columbia River that was an orcharding community, fruit community, called Wenatchee. It was down the river from the Grand Coulee, the second generator that was being built, the second phase of the Grand Coulee Dam. So a lot of people who had been migrants got to get off the big L, right, of working crops from Texas on up to Washington, and then back home. So Wenatchee was a boom town in 1949. My father was an insurance adjuster, so the only place we could rent was a garage that previously had been used to house chickens in 1949.

PM: Unbelievable.

DO: There was literally nothing in the town to rent. And it was great because there were a lot of people from the south and the southwest who all played or listened to country music. So my father was a jazz collector. So those influences which are still predominant influences are the sound of early jazz and Hank and Lefty Frizzell, and all those people that would have been radio stars then, as well as the pop music that was playing, Rosemary Clooney and whoever else would have been -- Frank Sinatra -- would have been on the radio.

So it's an interesting sort of panoply of music contexts that are there, because you'd go play at kids' houses, and there'd be guitars, which at the age of six or seven was an iconic and magical instrument. At the age of 63, it still is.

PM: [laughs] Isn't that the truth.

DO: Yeah. I mean, I didn't get one. I probably would have gone on to something else had I gotten a guitar at an early stage and gotten it out of my system. But I had to borrow one at the age of 19.

PM: You mean you didn't have one until then?

DO: No, no.

PM: Were you playing something else before then?

DO: Well, I mean, in junior high school I played clarinet.

PM: It was very popular in that time period, right?

DO: Well, it was a way to learn music.

PM: Right.

DO: We had a piano for a while, but unless you have somebody that can ease you into the piano, it's a really formidable instrument. If you don't have some way to anchor yourself into it, which is either by song or something that continually rewarding and helps you grow, just playing scales isn't going to do it. So I like playing music, just because I love music, but it wasn't really rewarding. At least with a guitar within a fairly short period of time and effort you can get three chords. You can get five. And with five chords the world opens up to you.

PM: As long as you don't want F to be one of them, you can get five.

DO: Well, that's why God invented a capo.

[laughter]

PM: Because by 19 you were probably starting to see a couple of shows that would electrify you into the future.

DO: Well, I saw early rock 'n' roll. In Wenatchee, the venue was the D & D Roller Rink, which had a little small band shell in it.

PM: Excellent acoustics, no doubt.

DO: It was pretty good. I saw Gene Vincent and Little Richard and Fats Domino there.

PM: Holy jeez.

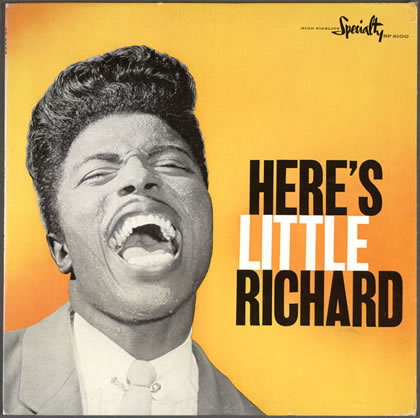

DO: At the age of 13, the first record that I ever bought was that Specialty record of Here's Little Richard. I still have that record. That, I think, is one of the greatest rock 'n' roll records ever made, right in there with anybody you want to talk about. You can hear it today, and I don't think it could have been more than a 3 track machine, and probably not even a 3 track machine.

PM: Right.

DO: You hear Earl Palmer's sound on drums, and the way that whole thing is miked and recorded, it just pounds.

PM: Just a force of nature, Little Richard.

DO: Oh, yeah, he's from Mars. He'll always be from Mars. It just doesn't matter. But in that period, when he was sort of really insular, right, and he was just complete within himself, and he had that voice that was just straight out of some kind of church I never got to go to.

PM: Were you one of several children?

DO: I'm an only child.

PM: What was your personality then as a young person? Were you recessive, or an outgoing fellow?

DO: I actually was both. I was reasonably popular with the jocks and reasonably popular with the hoods. And that was kind of how you work both sides of the street and could have friends on either side, because they were both interesting. It was a small town. The primary avocation was sports, so you had to be involved in Little League, you had to play whatever you could play, because anything--

PM: And what could you play?

DO: I could play baseball. I wasn't bad at baseball. I was pretty light for football. I'd actually get abused in football because I was only like 135 pounds. Even when a 150-pounder hits you and you're only 135, it's still a big edge at that age.

PM: And basketball, no?

DO: I love basketball, but unfortunately I was not very good at it. It was probably the sport that I loved the most and had the least skill and aptitude. I mean, I don't really regret it, I just didn't have it. When I got to junior year I was able to play tennis a little bit just because I had a little bit of backspin. But I quickly got over sports and I was interested in beatniks.

PM: Right. How did you get your first break?

DO: It's a wonderful story, I'd love to tell it.

Some friends of mine were in a band called the Daily Flash. And they were signed on Parrot. And they had a large following in Seattle. They were kind of like Seattle's answer to the Byrds. But they were more complex in some ways. They were kind of one of the first rock fusion bands. They played Herbie Hancock's songs like "Cantaloupe Island," and they played "Air Raid" by Grachan Moncur III. I mean, who knows what that is?

PM: [laughs] I never heard the man.

[learn more at www.grachanmoncur.com]

DO: No, I mean, they were very hip, and yet they'd still play great dance songs and all of that. The ones that are living are still good friends of mine.

So they had a deal, and they were all going down to L.A., so I rode in the car with them and went down there the first time, and stayed for less than a month. I was just so provincial in nature, L.A. was overwhelming, to say the least. And I didn't have a car, and I didn't have any money.

I came back to Seattle, and there was a local record company there, and somebody recommended me as a writer, and so we cut some singles. It's kind of where I got my early start. And then I went back to L.A. again with one of the guys who had been in that band, the Daily Flash. And he still had a relationship with Greene & Stone, who had been their managers. And Greene & Stone managed Sonny & Cher, The Buffalo Springfield, Dr. John, and Iron Butterfly. They were regarded in several ways as keen appreciators of talent. They were able to see talent pretty clearly -- certainly Charlie Green was. They were not considered scrupulously honest. But that's neither here nor there. They didn't take any of my money.

PM: Well, then, it's neither here nor there.

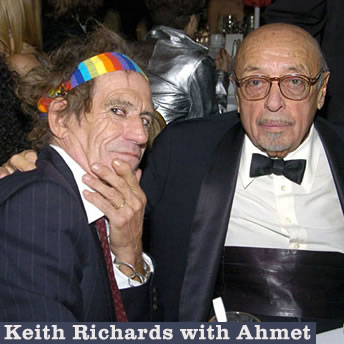

DO: That's right. So we would go and hang out with Charlie Greene in the afternoon. He was very much a character, just a classic New York street hustler, just really good at it. And one day somebody calls him on the phone, and we're just in there, we've been hanging the -- kibitzing with him. He was funny. And he said, "Get out your guitar. Get out your guitar. Go on." He said, "Ahmet, I want you to hear this kid."

PM: Wow.

DO: So I just played two songs into the phone. Charlie holds the phone, and I play the songs.

PM: He's on the phone with Ahmet Ertegun?

DO: Ahmet Ertegun, that's who he'd done deals with. That's how -- Iron Butterfly is on Atco, Buffalo Springfield are on Atlantic. Dr. John is on Atlantic, I think maybe the Cotillion label or Atco label -- I don't know which. So he has a relationship with Ahmet. Ahmet was -- is still very much a very keen appreciator of talent and of the people who see talent. It's something of a generational thing, but it's also something that was specific to very few people in the music business who had the true A & R skill. Clive still has it. There were others that had it, that were really classic A & R men, who went out and saw talent and signed them and brought them in the studio. Ahmet was like that.

PM: What did you play him on the phone? Do you remember?

DO: Yes. "Good Time Charlie's Got the Blues," and "Steel Guitar." I don't necessarily think those are my best songs, but they seemed to be of a piece, in a sense.

PM: Right.

DO: And they were easy to play. So the next day Ahmet comes. And I don't know who he is at the time, but David Geffen is with him, and somebody else. And they think that we're a band, right? You know, the bass player from the Daily Flash and -- that we're going to be a band, and we want an advance to get some equipment, a van, and we want to go make a record and--

PM: Get on the road.

DO: Standard deal.

PM: Yeah.

DO: So Ahmet says, "Fine." Gives Charlie some money, which we don't see much of. Charlie gives us enough for rent, but I don't think he gave us much more than $500. And he probably got 5,000, or whatever.

PM: So he'd deduct his finder's fee right off the top.

DO: Right off the top. So that had nothing to do with us. I mean, that wasn't our business, and we weren't told about it. Unfortunately, one of the guys has a drug problem, and we don't have any equipment, we don't really have a drummer. So it just starts to fall apart.

PM: Right away.

DO: And I don't have any money. I can't stay there. So I come back to Seattle. A few weeks later I just get a wild hair, and I call Ahmet.

PM: Atta boy.

DO: And I said, "Remember, I played over the phone to you in Charlie Greene's office?" "Oh, yeah." He said, "Well, send me some demos. Send me some songs." And so I sent him some stuff I'd recorded on a Webcor. You wouldn't want to be in the same room listening to that stuff now.

PM: Just you and a guitar?

DO: Yep. So I didn't hear back, and so I called back a couple weeks, three weeks later. And I mean, the great thing about Ahmet was that he'd always take your call.

PM: Amazing.

DO: I mean, he'd take your call if he knows who you are and it isn't a cold call. You never got that heavy screening and going three people deep to get to him.

And he said, "Yeah, we listened to it. We didn't hear too much on it." I said, "Well, you heard 'Good Time Charlie' and 'Steel Guitar,' the same two songs I played for you over the phone." And off the phone he asked his assistant, "What were the songs that we said we liked?" The guy says, "Good Time Charlie" and "Steel Guitar." He said, "Okay." He said, "What do you want to do?" I said, "I want to make a record, and I need some money." He said, "How much do you need?" I said, "I don't know. Maybe about $5,000 or something." He said, "I'll give you ten, and we'll go down to Muscle Shoals and cut a record." Well, there are not very many people that understand what that means.

PM: That's unbelievable!

DO: A lot of people don't even really understand what Muscle Shoals was. It was just this kind of garage that had been turned into a studio with some of the finest tightest players that ever came out of the south, just -- they couldn't get out of the pocket if they tried.

PM: Right. continue

print

(pdf) listen to clips

puremusic home