A Conversation with Charlie Chadwick (continued)

CC: Oh, and look at this: All the people who've tried to do this over the 300 years the bass has existed have failed.

PM: And there've been plenty of them.

CC: Plenty of them. I've seen a bolt-on upright bass neck. There's a guy in New York right now, I've visited his website, he advertised that he'll take your neck off of your bass and install this appliance that he's made, a metal appliance that allows you to insert the neck back into this little sleeve and bolt it in, so your neck becomes a detachable neck. So there're people working on this problem. It's a huge problem.

People want to use their own bass, they want an acoustic instrument. They want a full-size normal-looking instrument. They don't want little skinny instruments, they don't want things you have to amplify all the time. They want something that has their strings, their action, their feel, their pickup. That's what the market wants, that's what us bass players want. We don't want a second bass, that, "Well, I use my travel bass when I travel, but it kind of sucks, but" -- you know?

PM: Yeah, I just did a gig in Guatemala with my travel guitar. I'll never do that again.

CC: No, it's not worth it. But for a guitar player, you have the option, well, I could bring my guitar. At least you can carry it on and keep an eye on it. It's not like you're throwing it to the wind.

PM: Right.

CC: The upright bass player doesn't have the option. There's no carry-on bass.

So I thought, where are all the points of deconstruction? You can take the neck off, that seems pretty logical. The problem is -- and this might not be obvious, looking at the bass -- but the end of the fingerboard to the top of the scroll is longer than the body.

PM: Right.

CC: Right. So okay, you've taken the neck off. Taking the neck off is not a big deal. Putting it back on is a big deal, it's hard.

PM: Yeah.

CC: But let's say you took it off. Imagine, for once, that the strings and the tailpiece are still attached to it, and the tuners, and the fingerboard, and it's longer than the body. You've got to have a case for that, and it's got to be pretty well protected, because there's a lot of things that can get screwed up.

PM: Yeah.

CC: And you've got a pretty good sized case already That's a pretty good sized thing. It's not as big as the body. Well, then you've still got the body to put in a case, and there's two cases now. And you've got to figure out how to put the neck back on. And the fellow that I was referring to in New York has figured out a way to bolt the neck back on. And indeed, that's a typical repair on basses. You'll see a lot of old Kay basses, and you'll see a little plug on the heel of the neck where it attaches to the body. And what you're seeing is: that neck broke off. The repairman glued the neck back in, then took a big lag bolt, and lag bolted it right through the heel into the neck block.

PM: Wow.

CC: Typical repair.

PM: He turned it into a modification.

CC: Yeah, but you can't take it off, it's still glued in there. So the issue is, for me, from an engineering point of view, you're dealing with tremendous forces that are trying to yank the instrument apart. And my thought was instead of trying to resist those forces, what if those very forces were the ones that held it together? And that was my line of thinking.

PM: Right.

CC: So I said, instead of resisting 300 pounds of pressure, why not use 300 pounds of pressure to drive the neck into the socket? I like that. That made more sense to me.

PM: The Aikido approach.

CC: Yeah, let the energy work for you.

So I started the project, and I had three goals that I insisted upon. One was that there were no tools and no bolts and no wrenches and no screws, and no nothing, none.

PM: Wow.

CC: Because you're likely to lose something -- Dave Spicher was playing a gig with Pam Tillis up in Alaska, and he gets ready to go on, he goes, "Where's the bolt for my Eminence?" The Eminence has a bolt, and he couldn't find the bolt.

PM: Oh, my God.

CC: He'd left it at home. He's in Alaska. He had no bass.

PM: He left the bolt at home.

CC: Yeah. And I thought, okay, no bolts, no tools. That's just rule number one.

I also wanted the bass to be visually unchanged, so that even if you handed it to the bass player and he'd play a big, he wouldn't know that there was anything funny about it. No modifications that were obvious.

And the third one I gave up, I just threw this one away, my third one was that it was reversible, meaning that you could undo it, glue the next back in, and you're back at the same bass you started with, didn't even damage the instrument in any way. But I gave up on that.

PM: [laughs]

CC: That was impossible. It was a lofty goal. The idea was you could take any high quality carved instrument and modify it and then undo it later. I have a great respect for fine instruments.

PM: Right.

CC: But I realized I couldn't get around it -- the design requirements. If there's a way to do it, I couldn't think of it. So I stuck with one and two. And you'd be surprised at the hardest part. The hardest part of this instrument was the case. And the other hardest part of the instrument was the no straps and no tools to pack it up. Because it's one thing to hold it together without tools, I got that figured out pretty early on. The problem is: How do you pack it up for travel without using any straps or holds or Velcro? How do you fasten all the loose pieces together in such a way that there's no tools and no -- you know what I'm saying?

I just kept wrestling with that one. I found ways of strapping a piece -- well, I could violate my first rule and have a few snaps and straps and things like that. It just wasn't appealing to me. And I had a removable neck, and I early on realized that if I remove the fingerboard that really reduces the length of the neck and the fingerboard, because the fingerboard hangs over almost two feet off the edge of the neck.

PM: Two feet?

CC: Well, now I'm exaggerating. More than a foot. So I took the neck and fingerboard apart. And that solution has been working ever since. I love it. The first solution was to have a removable neck. And every time I put the neck in the neck joint was just like a loose neck. You've had a loose neck on a guitar? It's awful. And a loose neck joint on the bass is worse, because that's the frequency that's compromised by the loose joint.

PM: Yeah, you lose your resonance.

CC: Yeah. It's got to be "coupled," is the engineering term.

PM: Right.

CC: So I kept thinking about that. No, this neck joint sucks, it comes off, it goes back on, but when you put it together, the bass doesn't sound good, it sounds wrong. So I kept working on that. But all the time I'm playing this removable neck, I'm looking at the body and going, "There's a lot of air, empty space in there. If I could just somehow pack the neck and fingerboard into the body, I would save so much room traveling." I kept thinking about how to get it in there. I thought about a drawer that kind of came out the side of it.

PM: [laughs] Yo.

CC: I kept thinking about how to get the neck in there. And I just couldn't figure it out. And I had a gig one night, and this guy had one of these fiberglass guitar cases. It wasn't a Calton, but something like that. It was Tommy Emmanuel's case, as a matter of fact. And it was covered in some kind of like -- it looked like a space suit kind of thing. It was a really cool looking case. But he opened up the case, took his guitar out and shut the case, and I went oh, shit, that's it. You just open the body like a suitcase, take the neck out, fold up the neck and everything, shut the body.

And then I went, "Oh, wait a minute, the sound post! That wouldn't work, it'd just fall over. Damn it." But I suddenly was going down the right road. How do I get into the body, work around the sound post issue, and then I could store the neck in the body.

PM: Wow.

CC: I thought, that's got to be it, got to be it. And then I'm thinking, well, what happens when you cut the body? My God, that's probably going to ruin everything.

PM: Right. Yeah, certainly threaten to.

CC: But there's no way to know until you try it.

PM: Right.

CC: So I got a --

PM: Scalpel.

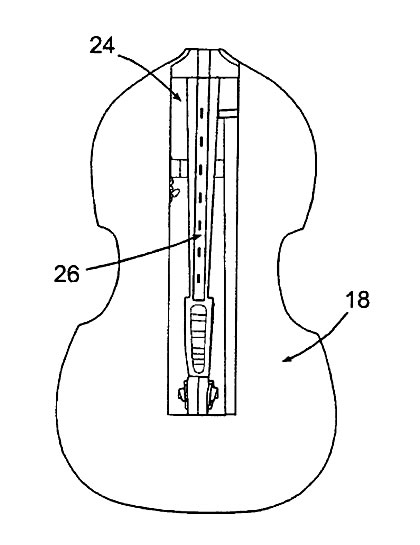

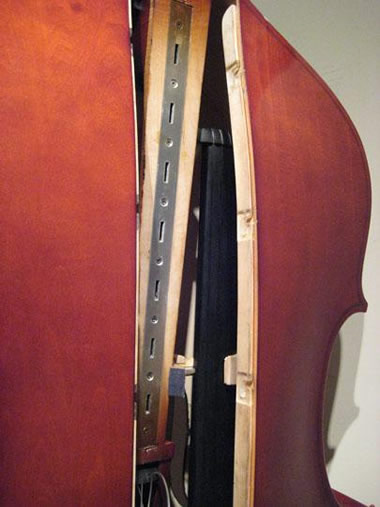

CC: I got a saw, and I cut a big enough hole in the back that the neck and the head stock would swing down into the body, but out of the way of the sound post. The sound post is off to the side.

And it all worked out pretty good. I thought, well, this works. But the problem that you immediately run into: Imagine that you take a curved piece of wood, and you cut it, it deforms, and it won't fit back together.

PM: It won't reform, right.

CC: No, it won't, because there are tensions and so forth. So I thought now I'm really screwed, now I can't cut the back out because it will deform. Then I thought, well, what if I braced it in such a way that the braces brought it back into its original shape? Okay, that would work. Right? Well, there are many problems with that. I mean, how do you put the door back in? I could hinge it, but you can't hinge something that's curved, hinges are straight.

I'm going on and on like this, thinking I got the right idea here but somehow I can't see my way past this. Well, the solution was to brace the bass like you brace a guitar, it's basically a ladder brace. The braces run down this opening, and the braces are detachable.

PM: Oh, the braces are detachable.

CC: Exactly. And the way I detached them is I have a simple compression fitting. There's a little nylon pin that fits into a slotted groove, so you put the door in, you line the pins up with the door, and push it down, and as it goes down it starts to compression fit because the slots are on a 10 to 15 degree angle, so as you push the back down it just sucks itself right in into the braces, the braces are locked together, and the whole back and the door are compression fit and are coupled mechanically.

And it worked perfectly, no tools -- it fit all of the requirements. It opened up the bass.

PM: And it did what a brace is supposed to do.

CC: Yeah. It strengthened the back and recoupled the back and the door.

PM: Wow.

CC: And they're made of spruce, brace grade spruce, and they are light. What I didn't know is, well, okay, that's good, what is it going to do to the bass sound-wise? So I got one of my good Neumann mics out, and I set my preamp up, and I recorded the bass before I cut it, cut it, braced it and put it back together, and recorded with again and analyzed the wave file, the amplitude and the wave characteristics.

PM: Wow!

CC: Yeah, I wanted to make sure it didn't change it.

PM: That's beautiful.

CC: So all that worked out pretty good.

PM: So how close was that wave form?

CC: Well, an interesting result was that the bass had a longer sustain once I put the braces in.

PM: Wow!

CC: To a bass player, that's good.

PM: That makes sense.

CC: Yeah, sustain is good unless you're playing salsa music you want your bass to boom, boom, boom, boom...

PM: Yeah, and you got to do with it your hand.

[laughter]

CC: Yeah, but long sustain is a better thing, and I think it's just because there's a little bit stiffer back. A little more mass in the back means that you're transferring -- you're not losing energy in the back, it just throws it right back at the top. So I believe -- I'm not a Luthier by trade, but I did notice that change in sustain, and I thought, well, that's a good thing.

print (pdf) listen to clips puremusic home