A Conversation with

Paul Burch

(continued)

PM: So for readers who may not be acquainted with his cultural contributions, let's talk about your friend, the late John Peel.

PB: Well, Peel was born in Liverpool, and had a very interesting life. He moved to Dallas at one point, which was where he met the Kennedys.

PM: Wow.

PB: He worked for a radio station there. He was living in Dallas when Kennedy was killed. He had told everybody for years that he was in the building when Oswald was being taken from wherever it was, the Dallas jail, to some other jail.

PM: Holy crap!

PB: Yeah. He passed right by him on his way to being killed. And he had told everybody this for years. And then right before he died, he was watching a documentary that maybe the BBC was doing, and he actually saw himself, he saw some footage that had never been seen before of Oswald's journey down the elevator to the basement to be taken to a different jail.

PM: And he saw himself on the film.

PB: And Oswald passes right by Peel and Peel's buddy. But that's how he got his background in country music. He was living in Dallas at a really interesting time. I'd have to double check, but I think it's when Jack Clement was in either Houston or Dallas. When Jack Clement got fired from Sun Records, I think he was in Nashville very briefly and then moved to Dallas, and started his publishing company. And that's where he got the song, "He Stopped Loving Her Today"--

PM: Oh, my.

PB: Or is it "She Thinks I Still Care..." Anyway, Dallas was a hopping scene at the time. Because didn't Papa Daley have his record label there still? And there was a Jamboree there. So Texas was really happening, and he was there at that time. But the big thing with Peel was that I believe he started off in pirate radio stations, which was the big thing in England, because the BBC wouldn't play rock 'n' roll. So bands like the Stones and the Beatles, they got their rock 'n' roll from pirate radio stations, which were stations literally on ships that were in international waters and broadcast the American rock 'n' roll and country and R&B records.

PM: That's incredible. I didn't know that.

PB: And I think he was the first BBC disc jockey whose job it was, really was, to promote rock 'n' roll. And he got that in, I think, 1966. And he started this series called The Peel Sessions, where everybody who was new and hip would come and do his show. In fact, there's a great double record of Jimi Hendrix at the BBC. And a lot of it is hosted by John Peel.

PM: Wow.

PB: And everybody knew him. He told this hysterical story of how when Yoko Ono was having a miscarriage and needed a blood transfusion, Lennon was calling everybody who--specific people to see what their blood type was, because he wanted the blood that Yoko was getting for her transfusion to be from--

PM: A cool person.

PB: --a cool person, exactly. And Peel was called to see what his blood type was, to see if it would match, because Lennon wanted him to contribute to the blood transfusion.

PM: But he wasn't a match?

PB: I don't remember. I don't think he was. I don't know, but he had a wonderful cynical attitude about it. And when punk music came, the Undertones, and The Damned, and 999, and all those groups, he was a big, big, big supporter of all that stuff, and all the glam rock stuff, the New York Dolls. He was a huge, huge supporter of the White Stripes. In fact, he told a lovely story where he went out to dinner--he would do some shows at the BBC, and then record some shows at his house, where he had a broadcast booth set up in his library, which is where I met him. And he said the White Stripes came and he had dinner with them. And Peel was talking about how much he--about seeing Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent, and what a great show that was, and talking about all those great rock 'n' roll guys. And then when the White Stripes came in and did a session, they did an Eddie Cochran song and did a Gene Vincent song right on the spot--

PM: Whoa!

PB: --which of course endeared him to them.

PM: Right.

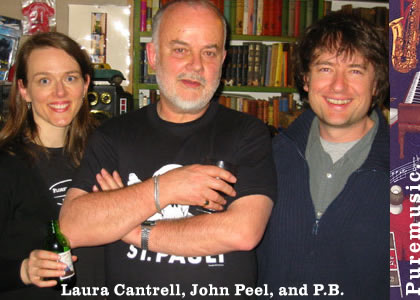

PB: But he was just a tremendously sweet guy. And he was a huge fan of Laura Cantrell, and invited Laura to do one of these very special shows at his house. And so I came along, and that's how I met him.

So he was really responsible for making rock 'n' roll accessible in England, and he was sort of the prime source of what was cool. If you played Peel, you were cool. And it really made careers. Some stuff he would say no to, and a lot of stuff he didn't get to. But if you were played on his show, that was really a sign of making it to the larger world of hit music. Country music, unfortunately, even though he loved country music, completely missed that. And I'm sure he would have welcomed country music. But it was just the rock and pop world that really understood who he was.

PM: Right.

PB: And there are, unfortunately, a lot of American artists still who refuse to even look into traveling to the UK, and so they have no idea who he was. But the people who do know realize that the rest of the world listened to the BBC World Service. Country artists, for instance, don't regularly tour the UK. The only guy who ever went over there much in the last twenty years is Garth Brooks.

I've actually sold more records in England than Dierks Bentley. I think they spent a quarter of a million dollars trying to promote him over there. And I'm sure I've sold less than 5,000 records over there. But I think he's sold in the hundreds. He sold so little, considering the amount of money they spent.

PM: They don't like that kind of music over there.

PB: Oh, they love it all.

PM: I mean, but they don't like mainstream country, do they?

PB: Well, but it is played, though. There is a place for it to be played on the BBC.

PM: Oh.

PB: And they may not like it, but it's entertainment. If it's entertaining and a good show--I mean, Alison Krauss doesn't go over there nearly as much as she should, I'm sure.

PM: Right.

PB: And Lucinda, she's got to take the Queen Mary over, or something, because she won't fly.

PM: She won't fly?

PB: It's just that all these people have a real hang-up about going over there. But it is the place, really--I mean, it's really the New York of the music world: if you can make it there, you can make it anywhere. You're with real music lovers who are not really interested in press releases and all that stuff. They want to know what's good. And that, more than anything, has really affected the way that I think about music. You have to be able to live with it and know that you did the very best, and that it's something that can grow; because you just can't count on the business, so called, for your props, so to speak.

PM: Right.

PB: It's nice when they come, but it's going to come on their terms, not yours, so the only thing you have to count on is being able to do what you love to do.

PM: Now, on top of being a fan and a supporter of Laura Cantrell, did Peel later become a fan of your music as well?

PB: I think so. I mean, he played a song of mine on his show the very next week, or something like that. And I was actually in between records, at the time, so I didn't really have a chance to share a new release. He died about a year ago, so I didn't have a chance to revisit that again. I think he might have been. He was really supportive. So I have a very nice memory of it.

PM: And now a very nice song, to boot.

PB: Well, thanks.

PM: It's a beautiful testament.

PB: I was wondering if somebody else had written a song called "John Peel."

PM: It's the first one I've heard. continue

print (pdf) listen to clips puremusic home