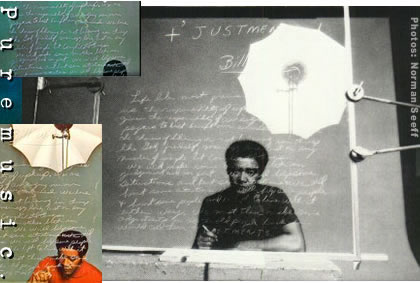

A Conversation with Bill Withers (continued)

BW: So, the record business has a sort of strange way of evaluating stuff.

PM: Didn't your record company overlook "Ain't No Sunshine" as the first single?

BW: That's a good example. On your first single, they would put the song they thought was most likely to succeed and on the B-side of it they would put a song and say, "Well, we're not going to need this later, so let's put it on the B-side." My first song that anyone knew me by was "Ain't No Sunshine." That was a B-side. When the single got out and away from the record companies, disc jockeys turned it over and that's how my career got started.

I think record companies are a bunch of guys trying to figure out what they think somebody else will like. And if you really think about it, other than Clive Davis and a few people like that, the people who really do that A & R thing are pretty transient. They're there for a couple of years. Somebody gives them a lot of money and they blow up, and then some of them go to rehab. [laughs] Then something new comes out that somebody likes and then everybody starts looking for one of those.

I've had people say over the years, "You know, we need something like that 'Grandma's Hands.'" Well, shit, I only had one grandmother. [laughs] You know what I mean? There ain't nothing else like that. [laughs]

I don't know, maybe I'm old and kind of crabby now, but there are a few people with a lingering knack for figuring out what the next thing is going to be. When rap came out, you couldn't give it to a major record company. Think about that. There were all these predictions that it was this temporary thing that was going to go away, and now, financially, a large part of the music business is sustained by these kids talking. And sometimes using sections of old records. I've certainly enjoyed it. Things like Black Street using a little bit of one of my songs and making a hit. It's fun for me. But, I don't think anybody knows what somebody's going to like.

PM: There are so many examples in the history of pop music of career-making songs starting out as B-sides or being initially overlooked.

BW: Here's another one. I heard a song that I thought, "Man, I wish I had written this song!" It was a Roberta Flack song called "The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face" [written by Ewan MacColl]. It came on the radio for about a week, then it went away. Years later, Clint Eastwood made a movie, Play Misty For Me. They put the song in the movie and it was a hit. It was like a number one song. After it had been given up on when it was first released. I think people respond to music as it affects them. When somebody wants to dance, they just want to hear something that makes them feel like dancing. When they want to feel something more deeply, they look for something like that song.

PM: You've talked about the importance of seeing a visual image before you write a song. Can you elaborate on that?

BW: Let me flip that on you. I probably evaluate whatever I think I've written if it makes me see something. If there's some kind of visual thing that comes to mind. It's probably something that's maybe peculiar to me or maybe other people do it. Let me just sum up that whole question, because that's sort of a curiosity: how do you write a song? If I knew how to explain that, I wouldn't have time to talk to you right now, because I would be somewhere writing this best-seller book explaining how you write a song. I would probably never have time to think about writing songs for writing this book.

I think the best stories of how songs came about are made up after the song is written and people start asking questions about it. Really, for me, the process is, I was walking around scratching myself and something crossed my mind. Now, why it crossed my mind, I don't know. Why it crossed my mind instead of somebody else's mind, I don't know. The process for me is really being a conduit.

PM: It sounds like you don't like to analyze the process too much...

BW: I don't really want to know too much about how I do it. Because then it's not magic anymore. Early in my life, I was an airline mechanic, so my life was full of, you know, you attach this to that and you put so much torque on it, and this causes that to happen, and that causes the other, and your life is full of rules. And then you get over 60, and you can't eat nothing that's not green, and you got all of these things to deal with. So the one magical thing for me is when something comes from somewhere and I don't know where it came from. It just crossed my mind.

Probably because of how we are and what we feel, each of us individually, we probably have different data banks that we draw from. James Brown has his data bank. James Taylor has his data bank. Anybody that has written songs has some bank of feelings that they draw from, depending on their values and their personality and their intellect. I think the greatest songwriting tool is probably manic depression. I think some of the greatest uptempo things are written when somebody's manic, and some of the best ballads are written when somebody's in some sort of funk. When you're in a deeper feeling state. continue

print (pdf) listen to clips puremusic home