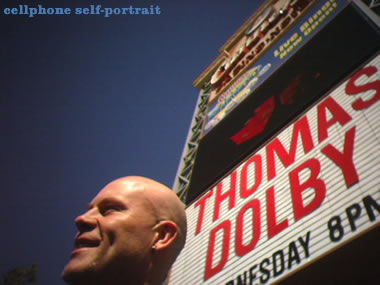

A Conversation with Thomas Dolby

(continued)

TD: I mean, it sort of starts with the economics, we don't need record companies anymore to finance our time in the studio, because we can do it in our back rooms. Nor are there these narrow windows of opportunity to get stuff released and marketed, because it used to be the label would sort of say, "Well, weeks three and four in July, that's when the sales force is going to be focused on your record." And basically that was the window of opportunity you had. If it didn't catch fire during that time, it was basically back to the drawing board for a year, year and a half. If the phone wasn't ringing off the hook during that time you just felt totally depressed. And you don't have that anymore; first, because there's such a diverse range of ways to get your stuff out there and distributed; and second, because shelf life is no longer something important. I put out a live album in December, and it's spiked several times since then. It has on weeks and off weeks, but I do an NPR interview and suddenly there's a new sales spike. And that can go on for years.

PM: Absolutely.

TD: I'm building, now, a digital portfolio of masters and compositions that I own and control. And that portfolio waxes and wanes, but it doesn't lose sight of you. It used to be so polarized in terms of hit or miss.

PM: And it's always available. You have it on your sight. You say, "Well, here it is. You can audition it, you can buy it, and you can do the whole thing right here."

TD: It's a way better state of affairs than I've ever seen before. It's kind of sad, but the press tend to focus on the woes of corporations and so on, and not on the fact that for music fans and for musicians this is just heaven on earth.

PM: Absolutely. I don't know what's going to happen to radio, but that also may not be something that everybody needs the way they did one time, either.

TD: Yeah, I think that's probably the case. To me, the record industry missed an opportunity 15 years ago to overhaul radio and its relationship to the industry. It drove me absolutely berserk, and still does, that if radio is my main source of finding new music that I'm going to like, then how come they don't back announce it? And how come even if they do back announce it, and I hear the name of the artist, I have to somehow remember next time I'm in Tower Records in the D section that that's an album that I want to buy. And then I have to spend 20 bucks on it to get the one song, and I have to take 20 minutes unwrapping the cellophane. It's just fundamentally a really bad product, it seems to me.

PM: Every step of the way.

TD: And looking back, there's no excuse for it. I mean, the nice thing these days with the internet is that, yeah, you can hear some music for free, but if you do get the warm fuzzies about that music, then the buy button is right there, and now you own it for 99 cents. And so the point of sale is right there where people fall in love with music. And that to me is just so much better a product, even apart from the vagaries of physical distribution and manufacturing.

PM: I think one thing that hasn't really been figured out is that unlike a tried and true and well-known artist like yourself, how does the new artist get himself in front of an audience so they can get warm and fuzzy about their music. I think that's not quite solid yet.

TD: No, it's not solid. And I don't know if it will ever be solid. But personally, I'd rather have "ameristocracy" than a system of filters in place where somebody gets to play God and decide what we do and don't get to hear.

PM: Right.

TD: And one of the worries when the internet came along was the fact that people in the industry were saying, "There won't be hits anymore unless there is the machinery in place." [laughs] And that's just not the case. I mean, there are still hits, but they're genuine hits because of popularity, not because some network executive decided that these were right for prime time.

PM: Yeah, hits where the people decide.

TD: Yeah. So you look at YouTube or myspace, or whatever, and stuff gets popular. And very often that coincides with--I've got three kids, it coincides with them mentioning a song or a video, an artist or whatever, and seeing it there on myspace, YouTube. I think it's great.

PM: Absolutely.

It's amazing that on the one hand you're a very perfectionist, highly considered producer; on the other hand, you're supplying audio to cell phones, which is maybe the most compromised sound that you can get on a device, but in this case, of course, your company, Beatnik, is responsible for the audio in half the cell phones of the world; it's unbelievable.

[laughter]

TD: Well, yeah, it is unbelievable. It was kind of an accident, frankly, because the company started out with very lofty ideals creatively, and it ended up that the one area where we could really make some impact, from a business point of view, was in cell phones.

PM: So is that, in general terms, the almost unspeakable success that it sounds like?

TD: It is pretty unspeakable, Frank, yes. [laughs]

PM: Bully for you.

TD: Somebody said to me the other day, "Didn't one of the Monkees invent liquid paper?"

PM: [laughs] Yeah, yeah, Michael Nesmith's mother, I believe.

TD: I think his mother, yes. So in future editions of Trivial Pursuit, perhaps I'll be in the same stack as Michael Nesmith.

PM: "Who was the unlikely inventor..." continue

print (pdf) listen to clips puremusic home