A Conversation with

Happy Traum

(continued)

HT: Video hit so fast. I thought it was a great idea to put lessons on video, and I sent out a questionnaire to our mailing list at the time, saying, "If we had these things in videocassettes would you want them?" And about ninety percent of the people wrote back and said, "No, don't bother. We're not interested."

[laughter]

HT: But then I decided, oh, I'm going to go ahead and do it anyway.

PM: For the other ten percent.

HT: Yeah. But really I knew it was going to be such a different way of learning, being able to see these guys. So I experimented. I found a guy with a camera and brought him to my house. This is, I guess, around '83 or so, '84.

PM: So it started with one camera.

HT: One camera--in my living room, again. And incidentally, the guy who did that camera work is still the main guy I work with in Woodstock.

PM: Get out!

HT: He does all the editing, he does all the shooting. He sets up all the shoots of all our videos here, anything we do in Woodstock.

PM: What's his name?

HT: His name is Cambiz Khosravi. He's of Iranian descent. He's a videographer and a documentary guy. And we just started working together, and it's continued for, what is it? Twenty-five years, thirty years.

PM: Unbelievable.

HT: Yeah, it's amazing. So we did some shoots in Woodstock in my living room. Kenny Kosek, and a lot of people came up. And then I decided I better get some really great people. So I went down to Nashville. And in one trip to Nashville, I recorded Sam Bush on video, Bela Fleck, and Mark O'Connor.

PM: [laughs]

HT: It was in three consecutive days.

PM: That was a good little trip.

HT: I mean, nobody knew how to do it, so it was kind of--everybody who was doing it was learning as we went along.

PM: Right, because it's a very peculiar thing to get up there and say what you play, and slow everything you're doing down, and try to get it in reasonable order, and all that.

HT: Right. But even from the technical aspect of the camera guys, the mixers, the guys who were--I mean, if you look at those tapes now, they're pretty funky looking, but they still hold up.

PM: Sure--they're historical documents at this point.

HT: Right, right.

PM: Yeah.

HT: So then it just picked up from there, and I started calling people and getting most people saying yes. We continued, and it just sort of built up. There's a limit to how many we can do every year, but over forty years, it sort of adds up.

PM: Because, after all, not only do most musicians need to cultivate any idea of an additional revenue stream, but there is frequently the notion present of giving something back to the community.

HT: That's right. And that's the other thing, for me. When you mentioned Alan Lomax--the thing, to me, about doing these tapes, is that in many instances you're documenting a person's accomplishments for posterity.

PM: Right.

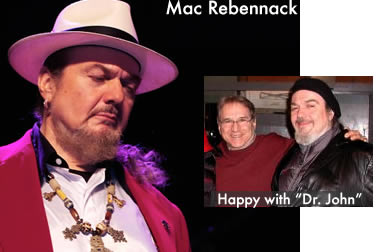

HT: You get somebody like Dr. John on piano, well, there are lots of records of him, lots of concerts, but he never talks about what he thinks about when he plays this stuff. And when he's not around anymore--and that's one of the things that attracted him to the idea, was that it adds to his legacy, adds to the record of his musical accomplishments. And I feel that very strongly. We have Bill Monroe, we have Ralph Stanley--he's still with us, but Bill Monroe is not, or John Hartford is not with us anymore.

PM: Right.

HT: So there's an aspect of their life and career and musical intelligence you wouldn't have if we hadn't taped them.

PM: Because it's played down, but there are many musicians that are very well-spoken, thoughtful people, who are concerned with much more than the gauge of strings they use. And when I watched the Tony Rice video, I was really knocked out by things like his statement about how he feels the folk movement legitimized bluegrass as an art form. I was knocked out by that. What an interesting line of thinking.

HT: That's right. That's very interesting, actually. Because people don't realize that in the 1950s and early '60s, guys like Bill Monroe were floundering. They had no place to play, they were not making any money. Rock 'n' roll had come in, and the southern guys who used to like their kind of music sort of turned to Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis and those guys.

PM: Pulled the rug out.

HT: Totally. And these guys were just scrapping around for whatever they could get, until along came the Newport Folk Festival, and the college campuses, and the kids who suddenly got this new interest in traditional music. And young people like myself were suddenly listening to them. The same thing with the blues guys, Mississippi John Hurt, or Son House, or Skip James, all those great blues guys who were just sort of passing the time, and suddenly here's this new generation of people that were all excited about their music.

PM: Yeah, all of a sudden there's a white guy on their porch with a microphone pointed at them. [laughs]

HT: Exactly. And suddenly they had a legitimacy that they didn't have before. And the same thing with the Cajun musicians. I went down to do the Cajun stuff with Michael Doucet, and I became friendly with Dewey Balfa.

PM: Wow.

HT: And Dewey is another guy who was so grateful that people in New York and California and Chicago and all these places were interested in this music that they grew up loving, but that nobody gave them any credit for outside of Cajun country in southwest Louisiana.

PM: Right.

HT: And you have no idea, these people were like the dregs of society to the people around them.

PM: Wow...

HT: And suddenly here's all these people saying, "You guys are great! This is a truly American art form, and it's something that doesn't happen anywhere else. And you're great players." And the whole Balfa family was just truly blown away by the fact that anybody cared, that people really valued what they were doing. I did gigs with them--not playing with them, but on the same show when they were first coming out of Louisiana in the late '70s. And they were totally amazed that all these outside people thought they were good.

So that's part of the driving force behind what I do here, is trying to legitimize--I mean, aside from the young players who are, as you say, looking for a little additional way to make some money.

PM: Sure.

HT: So it works in a lot of different directions. continueprint (pdf) listen to clips puremusic home