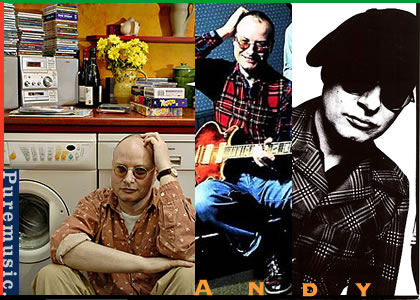

A Conversation with

Andy Partridge

(continued)

PM: I was concerned to read, though, about some mixing accident on that album that left you with a case of tinnitus and damaged hearing.

AP: Oh, boy!

PM: How did that happen?

AP: I would not wish that on my worst enemy.

PM: What kind of a mixing accident?

AP: Well, we had an engineer who was kind of clumsy. He was a nice enough fellow, but he was kind of clumsy. And he recorded a lot of earth buzz [that's English for ground hum, I believe] and stuff on some drum tracks, which we were all upset about, because it's stuff you can't do again. It's a one take, and that's it.

PM: Right.

AP: And we electronically cleaned up the buzz. And I was just checking to see whether we'd done a good job. And I was listening to a piece of silence on the recording, on headphones with the mixing desk at full volume to make sure that the buzz had gone.

PM: Right.

AP: And he was messing with the computer when he shouldn't have been, and he hit a wrong button. And he sent the sound of the snare drum at full volume--

PM: Oh no!

AP: --into my ears. I mean, the top of the mixing desk at full. Really as loud as you can go. My first thought was--after I kind of regained my senses, having visually blacked out--but my first thought was, "Christ, my headphones are so expensive, that's got to have fucked them up." And then I noticed that I could just hear this [whistles in a piercing fashion] sound constantly in both my ears. And oh, that was bad. That was twenty-four hours a day, this screaming, humming, whistling noise in your head. So for the last few months I've been spending every morning sitting in a hyperbaric oxygen chamber, which is like--if you don't know what it is--

PM: No.

AP: --it's like a diving bell. It's a big heavy iron sort of diving bell shape, with little porthole windows. And you go and sit in there, and they pressurize the air in there to the equivalent of you're like 33 feet under the ocean. And then you breathe pure oxygen for an hour through a mask. And then they depressurize you and bring you up again. And it's taken the volume of this screaming feedback down by about fifty percent.

It's a real pain in the ass to do it, because it takes up so much of each day. But I'm a desperate man, and I have to do it, because my hearing has been very, very damaged. And the worst thing is this screaming whistling tinnitus, which now that I know what it is, I would not wish it as a torture for anyone.

PM: Damn!

AP: Yeah. Within the first week of that incident happening, it's the only time in my life I've ever had suicidal thoughts, like as a way of, "I've got to stop this noise." You know?

PM: I can't imagine.

AP: Yeah, it's really tough. And I'm really being very optimistic about it, because if I didn't sort of go overboard on the optimism, I think I'd have checked into a lunatic asylum right now.

PM: And I think it's a big factor in getting healed, anyway, is just to keep a real positive edge on it.

AP: Oh, sure. But this treatment is kind of revolutionary, this hyperbaric oxygen treatment. The German Army discovered it, apparently, in World War II. They found that a lot of their soldiers firing machine guns and rifles and stuff with no ear protection, they were getting these traumatic tinnitus events. But you know what the Germans were like, they were just, "Let's see what happens if we do this. Oh, his head's exploded. Maybe that vas a leettle too much."

PM: Yeah, turn it down bit. [laughs]

AP: So obviously they stuck some soldiers in a pressure chamber and gave them oxygen. And the soldiers said that the tinnitus was going down. So yeah, it's a little bit of a revolutionary type principle. It's never going to get rid of it, but if it keeps it down, I can function.

PM: Wow. And I read also of a damaged tendon in the left hand. How did that occur?

AP: I've had the year from hell! [laughs] You know, have I pissed off God with that song ["Dear God"]? Maybe. Who knows?

[laughter]

AP: Dear Allah, I've obviously upset somebody. But I'd literally just got this Monstrance album done, all the playing finished, and woke up one morning and my hand didn't feel good. And the tip of my left hand ring finger was sort of hanging. I couldn't make it sort of go straight. And I thought, uh-oh, I've busted my ring finger in the night, banged it on the headboard or rolled on it, or something. But it didn't hurt. And I thought, "This is weird. It doesn't hurt, but I can't move it." And I went up to the hospital, and it was, "Oh, you've busted the tendon. It would have been good if you'd have busted the bone, because that takes five weeks to mend. But if you bust a tendon, that's going to be about five, six months."

PM: Oh! And what did they have to do, put it in a cast or something?

AP: I went to a hand specialist in London, because local hospital just said, "Come back in six weeks, and we'll take a look at it." Which is really the wrong thing, because you have to have a kind of a special splint made that pushes the tip up and back, so it can set more like a conventional finger shape again.

So yeah, on the health front, it's been a shit year. It's been pretty good for other things. But yeah, I'm really being tested this year. And weirdly, the two injuries, one was the finger that does all the work on the guitar, and the other was my ears.

PM: Yeah, the two things you need the most.

AP: Exactly.

PM: But I guess being able to take all the bits from various years and tie them all up in this collection, there must have been a satisfaction to that before all that stuff went wrong.

AP: Yeah, yeah. I was enjoying putting together the Fuzzy Warbles, in any case. I mean, the reason I did the Fuzzy Warbles series was a case of I was sick of being bootlegged.

PM: Ah.

AP: I was finding out that people were getting bootlegs of my demos and stuff. And bootleggers would even send me stuff. They would say, "Yeah, I just pressed up 1,000 of these albums of your demos, and thought you might like one, ha ha."

PM: Jeez...

AP: And it was really pissing me off, big time. And I thought to myself, "Well, obviously people want these things, and bootleggers are doing them. So I'm going to bootleg myself better than anyone else can." So it's really a case of if anyone is going to bootleg me, I can do it so much better. I've got stuff they're never going to have, I've got first-generation copies, I can remix and clean up old recordings. I've got thousands and thousands of hours of cassettes of run-throughs, rehearsals, practices, ideas. If there's any one person who can bootleg me, it's going to be me.

PM: Yeah. And for people who can't get enough, and there are plenty of us, it's a treasure trove. It's a really amazing collection.

print (pdf) listen to clips puremusic home